- 1. What is foster care and how does it work?

- 2. Foster kids are juvenile delinquents, right?

- 3. Does foster care lead to homelessness or vice versa?

- 4. Is there a connection with child trafficking?

- 5. Do foster parents make money off kids?

- 6. Is foster care as messed up as it looks in movies and on TV?

- 7. Is there an alternative to the current system?

- 8. Can I help foster kids, even if I’m not prepared to be a foster parent?

What is foster care and how does it work?

Foster care is a temporary living situation arranged by child welfare agencies for children who cannot live with either of their biological parents because of abuse, neglect, or other adverse circumstances. Children may also enter foster care if they become orphans. Once in foster care, they might live with relatives, licensed foster parents, or in group homes.

Unfortunately, too many kids are being removed from their homes and traumatized when early interventions can help keep families together. And there are not nearly enough foster parents to meet demand.

The way it’s designed now, the system puts a majority of foster kids at an economic and developmental disadvantage. For example, about one-third of the children who age out of foster care (at 21 years old in California) show signs of mental health problems, especially post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance abuse issues. They tend to have low levels of education and high levels of unemployment. All these setbacks add up to a high risk of incarceration, poverty, and homelessness.

Given that foster care creates so many obstacles for kids, it’s especially disturbing to note that black, Latino, and Native American children are overrepresented in the system. Intentionally or not, foster care perpetuates racial inequality.

The foster system and the flaws it encompasses are too large to ignore. In Los Angeles County alone, about 33,000 kids are in foster care. Meanwhile, between 2005 and 2015, the number of foster families shrank from over 8,000 to fewer than 4,000.

Foster kids are juvenile delinquents, right?

No.

Children enter the foster system because they have experienced trauma, not because they caused it. Still, over half of Americans mistakenly believe that foster kids are juvenile delinquents.

Though criminality doesn’t lead to foster care, the reverse is sometimes true: foster kids have to contend with overwhelming psychological stress, which often leads to undesirable outcomes, including incarceration. For example, a 2015 study found that 20 percent of youth leaving juvenile correctional facilities had once been removed from their homes because of abuse or neglect.

Foster kids who age out of the system (at 21 in California) with little to no family or financial support also risk getting caught up in the justice system as adults. A University of Chicago study of 600 former foster children found that almost 60 percent of males had been convicted of a crime.

These statistics aren’t meant to suggest that foster kids are broken, though. Instead, they illuminate all the missed opportunities to help foster kids succeed, from early childhood to high school and through college. Better yet, we could be doing much more to support parents and keep kids from entering the system in the first place.

Does foster care lead to homelessness?

Or vice versa?

Both. In 2016, about 10 percent of children who entered the foster care system did so, at least in part, because of inadequate housing.

But the foster care system aggravates the problem it attempts to solve: former foster youth represent a significant portion of the homeless, with The New York Times reporting that one-third of homeless young adults were once in foster care.

What’s more, about 20 percent of the children who leave foster care each year become homeless. If they struggle with mental health issues, have children, or identify as LGBTQ, they’re even more vulnerable to housing insecurity.

Most families in the U.S. don’t force children to become independent, financially and emotionally, at the age of 18 or 21. Foster kids are somehow expected to be the exception, even though they face a number of disadvantages, including lower educational attainment. Just over half of foster kids graduate from high school, and only three percent receive a college degree.

With so many obstacles and so few resources, it’s no wonder that foster kids often have a difficult transition into adulthood.

Is there a connection with child trafficking?

Sadly, yes. Foster children are much more at risk. In fact, in 2010, most minors arrested on prostitution-related charges in L.A. County were in the foster care system.

As legal adults, former foster children are two to four times as likely to engage in transactional sex as the general population. As Lauren Kirchner of Pacific Standard puts it:

The hard truth is that a lot of the risk factors for becoming victims of sex trafficking, or being recruited to transactional sex, overlap with the realities of life for many kids and teens in the foster care system: having teenage parents or parents struggling with substance abuse or mental illness; a history of sexual or physical abuse as children; and a lack of emotional, psychological, and financial support systems.

Do foster parents make money off kids?

No. Some people have the false impression that foster parents milk the system for money and leave kids with nothing—but in reality, there’s very little money to milk. In San Bernardino County, for example, parents are reimbursed for up to $820 (and often less) of their costs every month. That money has to cover food, clothing, housing, and other miscellaneous expenses.

Foster parenting also involves a lot of work, from the training to the paperwork to actually caring for the child. It can also be time- and transport-intensive, especially when it concerns the many children who meet weekly with their biological parents, doctors, and therapists. In a related problem in California, because there are too few foster parents, too many children are placed in foster homes far from their family, friends, and schools.

One foster mother did the math, and she found that the “wage” for raising a foster child is $1 to $2 an hour, if that. Even the most dedicated con artist would not do so much work for so little money.

Is foster care as messed up as it looks in movies and on TV?

It depends on the show, but foster care can be just as awful as it’s made out to be—just for different reasons than you see on screen.

Hollywood tends to mischaracterize the flaws in foster care by suggesting that just a few cold-hearted people (like unhinged foster parents or orphanage headmasters) are to blame. In reality, the whole foster care system is broken, and its problems originate right at the start of the process: with the trauma of children being removed from their families.

Once in the foster care system, these kids face obstacles at every stage. They struggle to obtain life’s essentials, like early childhood education, mental health care, and job preparation. Even when you account for the kindness of dedicated foster parents and social workers (whose stories rarely appear on TV), foster care is never the best outcome for a kid.

Is there an alternative to the current system?

There are a few. The best alternative is rehabilitating adult family members so that would-be foster kids can stay at home. By advocating for accessible childcare and early childhood education, organizations like the National Foster Youth Institute help reduce the pressures that can fracture families. For the same reason, the nonprofit Maryvale organizes psychiatric care and crisis-intervention services for entire families. Keeping kids with their families is the best-case scenario—an M.I.T. study shows that kids who stay at home have fewer problems with the law, teen pregnancy, and unemployment than those who go into foster care.

Those children who must enter the foster care system need more community support in order to thrive. California could also prioritize more funding for social programs in areas with high numbers of foster homes.

Can I help foster kids, even if I’m not prepared to be a foster parent?

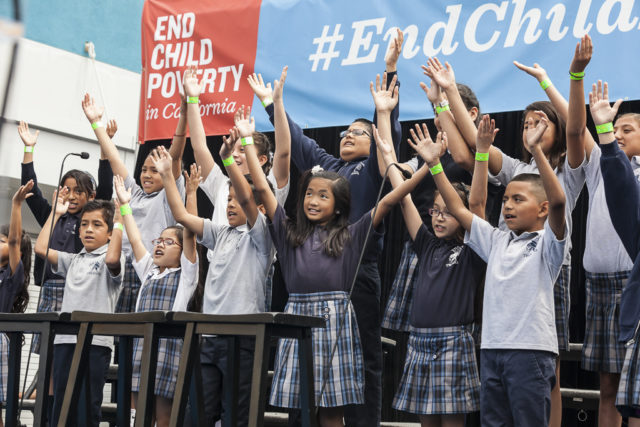

Emphatically, yes. You can join the campaign to End Child Poverty in California and help all families living in poverty get back on their feet.

You can call your member of Congress and help protect the provision of the Affordable Care Act that enables former foster kids to stay on Medicaid until age 26.

You can also become a court-appointed special advocate (CASA), mentor a foster child, or donate to a foster care agency.

Most importantly, you can stay informed!

-

1. What is foster care and how does it work?

What is foster care and how does it work?

Foster care is a temporary living situation arranged by child welfare agencies for children who cannot live with either of their biological parents because of abuse, neglect, or other adverse circumstances. Children may also enter foster care if they become orphans. Once in foster care, they might live with relatives, licensed foster parents, or in group homes.

Unfortunately, too many kids are being removed from their homes and traumatized when early interventions can help keep families together. And there are not nearly enough foster parents to meet demand.

The way it’s designed now, the system puts a majority of foster kids at an economic and developmental disadvantage. For example, about one-third of the children who age out of foster care (at 21 years old in California) show signs of mental health problems, especially post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and substance abuse issues. They tend to have low levels of education and high levels of unemployment. All these setbacks add up to a high risk of incarceration, poverty, and homelessness.

Given that foster care creates so many obstacles for kids, it’s especially disturbing to note that black, Latino, and Native American children are overrepresented in the system. Intentionally or not, foster care perpetuates racial inequality.

The foster system and the flaws it encompasses are too large to ignore. In Los Angeles County alone, about 33,000 kids are in foster care. Meanwhile, between 2005 and 2015, the number of foster families shrank from over 8,000 to fewer than 4,000.

-

2. Foster kids are juvenile delinquents, right?

Foster kids are juvenile delinquents, right?

No.

Children enter the foster system because they have experienced trauma, not because they caused it. Still, over half of Americans mistakenly believe that foster kids are juvenile delinquents.

Though criminality doesn’t lead to foster care, the reverse is sometimes true: foster kids have to contend with overwhelming psychological stress, which often leads to undesirable outcomes, including incarceration. For example, a 2015 study found that 20 percent of youth leaving juvenile correctional facilities had once been removed from their homes because of abuse or neglect.

Foster kids who age out of the system (at 21 in California) with little to no family or financial support also risk getting caught up in the justice system as adults. A University of Chicago study of 600 former foster children found that almost 60 percent of males had been convicted of a crime.

These statistics aren’t meant to suggest that foster kids are broken, though. Instead, they illuminate all the missed opportunities to help foster kids succeed, from early childhood to high school and through college. Better yet, we could be doing much more to support parents and keep kids from entering the system in the first place.

-

3. Does foster care lead to homelessness or vice versa?

Does foster care lead to homelessness?

Or vice versa?

Both. In 2016, about 10 percent of children who entered the foster care system did so, at least in part, because of inadequate housing.

But the foster care system aggravates the problem it attempts to solve: former foster youth represent a significant portion of the homeless, with The New York Times reporting that one-third of homeless young adults were once in foster care.

What’s more, about 20 percent of the children who leave foster care each year become homeless. If they struggle with mental health issues, have children, or identify as LGBTQ, they’re even more vulnerable to housing insecurity.

Most families in the U.S. don’t force children to become independent, financially and emotionally, at the age of 18 or 21. Foster kids are somehow expected to be the exception, even though they face a number of disadvantages, including lower educational attainment. Just over half of foster kids graduate from high school, and only three percent receive a college degree.

With so many obstacles and so few resources, it’s no wonder that foster kids often have a difficult transition into adulthood.

-

4. Is there a connection with child trafficking?

Is there a connection with child trafficking?

Sadly, yes. Foster children are much more at risk. In fact, in 2010, most minors arrested on prostitution-related charges in L.A. County were in the foster care system.

As legal adults, former foster children are two to four times as likely to engage in transactional sex as the general population. As Lauren Kirchner of Pacific Standard puts it:

The hard truth is that a lot of the risk factors for becoming victims of sex trafficking, or being recruited to transactional sex, overlap with the realities of life for many kids and teens in the foster care system: having teenage parents or parents struggling with substance abuse or mental illness; a history of sexual or physical abuse as children; and a lack of emotional, psychological, and financial support systems.

-

5. Do foster parents make money off kids?

Do foster parents make money off kids?

No. Some people have the false impression that foster parents milk the system for money and leave kids with nothing—but in reality, there’s very little money to milk. In San Bernardino County, for example, parents are reimbursed for up to $820 (and often less) of their costs every month. That money has to cover food, clothing, housing, and other miscellaneous expenses.

Foster parenting also involves a lot of work, from the training to the paperwork to actually caring for the child. It can also be time- and transport-intensive, especially when it concerns the many children who meet weekly with their biological parents, doctors, and therapists. In a related problem in California, because there are too few foster parents, too many children are placed in foster homes far from their family, friends, and schools.

One foster mother did the math, and she found that the “wage” for raising a foster child is $1 to $2 an hour, if that. Even the most dedicated con artist would not do so much work for so little money.

-

6. Is foster care as messed up as it looks in movies and on TV?

Is foster care as messed up as it looks in movies and on TV?

It depends on the show, but foster care can be just as awful as it’s made out to be—just for different reasons than you see on screen.

Hollywood tends to mischaracterize the flaws in foster care by suggesting that just a few cold-hearted people (like unhinged foster parents or orphanage headmasters) are to blame. In reality, the whole foster care system is broken, and its problems originate right at the start of the process: with the trauma of children being removed from their families.

Once in the foster care system, these kids face obstacles at every stage. They struggle to obtain life’s essentials, like early childhood education, mental health care, and job preparation. Even when you account for the kindness of dedicated foster parents and social workers (whose stories rarely appear on TV), foster care is never the best outcome for a kid.

-

7. Is there an alternative to the current system?

Is there an alternative to the current system?

There are a few. The best alternative is rehabilitating adult family members so that would-be foster kids can stay at home. By advocating for accessible childcare and early childhood education, organizations like the National Foster Youth Institute help reduce the pressures that can fracture families. For the same reason, the nonprofit Maryvale organizes psychiatric care and crisis-intervention services for entire families. Keeping kids with their families is the best-case scenario—an M.I.T. study shows that kids who stay at home have fewer problems with the law, teen pregnancy, and unemployment than those who go into foster care.

Those children who must enter the foster care system need more community support in order to thrive. California could also prioritize more funding for social programs in areas with high numbers of foster homes.

-

8. Can I help foster kids, even if I’m not prepared to be a foster parent?

Can I help foster kids, even if I’m not prepared to be a foster parent?

Emphatically, yes. You can join the campaign to End Child Poverty in California and help all families living in poverty get back on their feet.

You can call your member of Congress and help protect the provision of the Affordable Care Act that enables former foster kids to stay on Medicaid until age 26.

You can also become a court-appointed special advocate (CASA), mentor a foster child, or donate to a foster care agency.

Most importantly, you can stay informed!